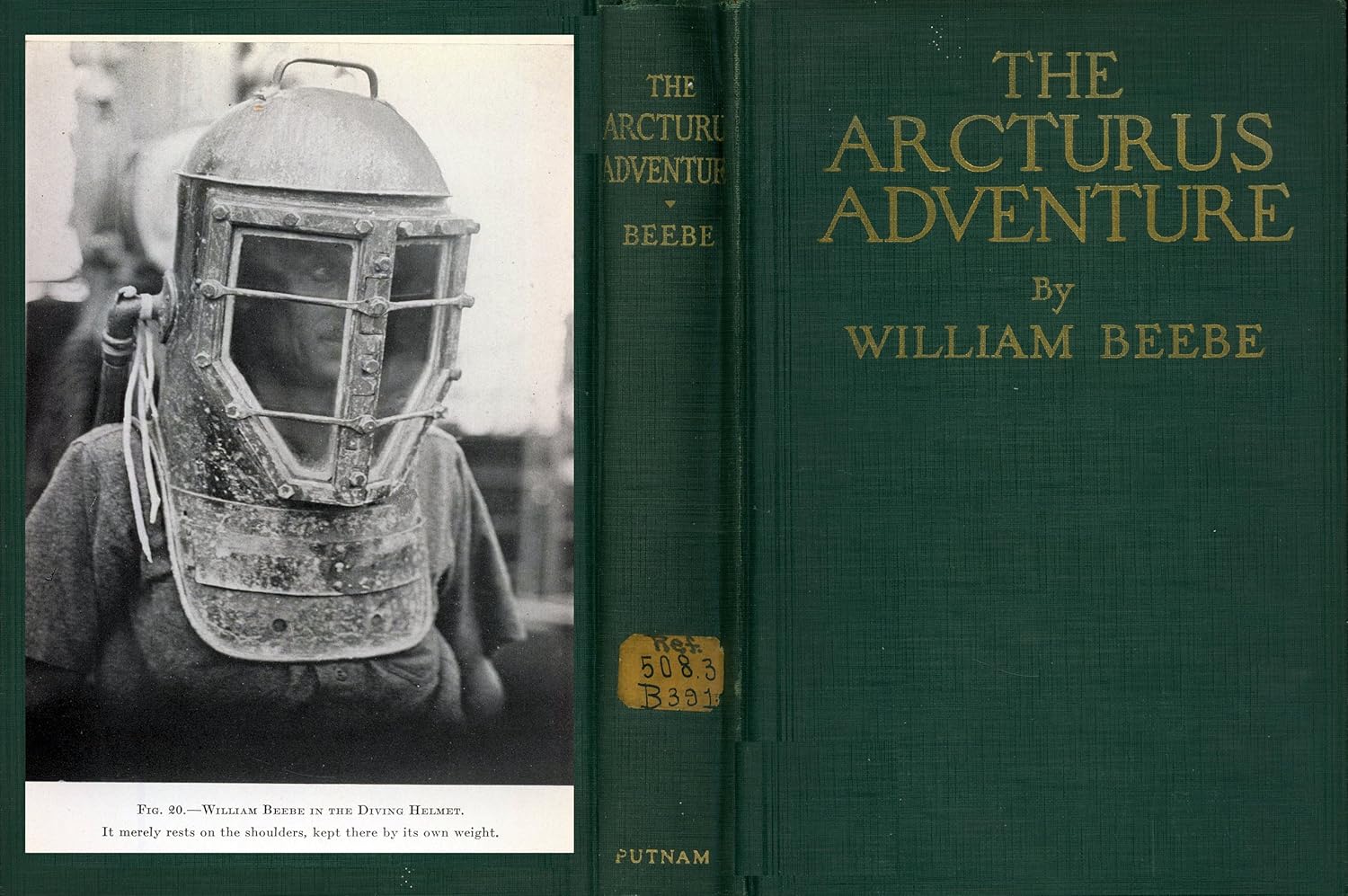

The Arcturus Adventure made William Beebe a household name. During the expedition, he used a diving helmet (seen above on the back cover of the book) to describe underwater regions never seen by humans. While Beebe was not the first scientist to work underwater with a diver helmet, and not even the most systematic, his popularity immediately marked him as the cutting edge of marine exploration to the general public.

My interest in the Arcturus Expedition stems from my current chapter writing. I'm working on the history of taxonomic illustration in marine science. Basically, I'm interested in how scientists illustrated their specimens. While the Arcturus Adventure is a popular work, it is also a scientific publication. Beebe and his crew spent much of the voyage dredging off the boat, pulling up as many deep sea creatures as they could, and somehow preserving these organisms for scientists and interested parties on dry land.

They did this in a variety of ways- and the different avenues they took to documenting these creatures is very telling to me as a historian. Here is the list of crew on board the Arcturus as it appears in the 1925 publication:

William Beebe- Director

W.K. Gregory- Associate in vertebrates (Elizabeth Trotter is his assistant)

L. Segal- Associate in Special Problems

C.J. Fish- Associate in Diatoms and Crustacea (on loan from the USBF)

John Tee-Van- General Assistant

William H. Merriam- Assistant in Field Work

Isobel Cooper and Helen Tee-Van- Scientific Artists

Ruth Rose- Historian and Technicist

M.D. Fish- Assistant in Larval Fish (wife of C.J. Fish, also on loan from the USBF, mislabeled- real name is Mary Poland Fish)

Elizabether Trotter- Assistant in Fish Problems

Dwight Franklin- Assistant in Fish Preparation

Jay F.W. Pierson- Assistant in Microplankton

Don Dickerman- Assistant Artist

E.B. Schoedsack- Assistant in Photography (listed as assistant in cinematography in subsequent editions)

Serge Chetyrkin- Preparateur

D.W. Cady- Surgeon

It's a varied group of people- but by far the largest group of specialists were those individuals brought on board to illustrate the work of others. Isobel Cooper, Helen Tee-Van, Dwight Franklin, Don Dickerman and E.B. Schoedsack were all included in the expedition for this purpose. On a scientific expedition, almost 30% of the crew was there to provide lasting images of the work. In addition to the individuals whose sole purpose it was to render accurate illustrations or materials in whatever form seemed most appropriate (more on this later), other members provided illustrations from their individual work. Charles Fish and Mary Poland Fish both illustrated their work on diatoms and larval fishes.

But hey, what were these people actually doing on board?

Isobel Cooper, Helen Tee-Van, and Don Dickerman were illustrators. They were in charge of drawing and painting specimens that Beebe felt were either special or important to capture in this medium. A scientist might ask one of these illustrators to draw and color a particular specimen that was integral to their work, or they might systematically go about drawing and painting specimens that appeared to be new or had interesting coloring. One might ask, why would you need illustrators on board? Couldn't you just bring specimens back that were preserved?

It was important that illustrators be on board for the journey because it is very difficult to preserve the color of marine organisms after their death. Because of this difficulty, many of the organisms these three individuals drew and colored were still alive when they did so. Below is a photograph from the voyage of Isobel Cooper illustrating a specimen from life.

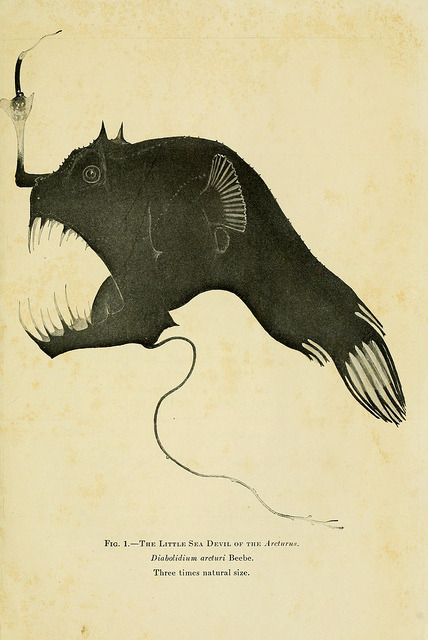

The first was caught in the open ocean and then placed in a special tank to be held still during illustrating. This way, Cooper would be assured she was not misremembering the color of the specimen. In addition to the difficulty of coloring, many of the most novel organisms identified during the expedition were deep sea specimens such as the little sea devil first described by Beebe during the voyage.

The "little sea devil" that Beebe pulled up during the voyage was illustrated by Dwight Franklin. Most deep sea organisms pulled up during dredging could not survive the handling and change in pressure (fish get the bends just like anything else that is pulled from the bottom of the ocean too quickly). Many of these forms died quickly, so having an illustrator on hand made it easier to accurately capture color and other features of these organisms on paper. For more information on Isobel Cooper- her grandson has a blog here that might be interesting.

In addition to drawing and painting, Franklin also made models of the specimens. In a photo posed similarly to that of Cooper painting, Franklin is busy in front of a aquarium fashioning a plaster replica of a specimen from life. Just as coloring was important to illustrators who were painting, it was equally important to individuals making casts and molds of organisms. In addition to these casts, Franklin and Serge Chetyrkin worked to find the best way to preserve actual specimens in alcohol so that they could be transported back to the New York Zoological Society. Preserving specimens did not merely require dumping them into preserving alcohol, but instead required careful preparation of the dead organism so that it maintained as much structure and color during preservation that was possible. Some organisms, especially jellyfish, easily dissolved in the alcohol and required special preparation.

In addition to illustrations and molds of fishes, Beebe also brought along a photographer/cinematographer. Ernest B. Schoedsack, best known for being the co-director of the movie King Kong, needed money for his next film so he signed on to document Beebe's voyage. He thought it would be interesting to shoot underwater. Many of his pictures appear in the Arcturus Adventure, one of which includes his future wife Ruth Rose diving at Cocos (in Bermuda) in 15 feet of water (unfortunately I can't find a copy of this picture on the internet). Schoedsack's supplemented the illustrators and preparateurs. When specimens were brought up and placed in an aquarium on deck, Schoedsack would immediately take a picture in case the organism died quickly or the color changed when exposed to the air. These photos became the basis of many of the illustrations and molds by Cooper, Tee-Van, and Franklin.

The whole crew of The Arcturus was amazing. On another day, I'll tell you about my new hero Marie Poland Fish, one of the pioneers of bioacoustics. If you're interested in learning more about William Beebe, check out this biography written by Carol Grant Gould. Gould is best known for co-writing books on bees and animal behavior with her husband Jim Gould. The story of Beebe's life, and especially his married life, is circuitous. Beebe did not want his second wife to write his biography after death, so he gave his papers (the few he didn't destroy) to his assistant and told her to seal them until she found someone she thought could write a proper biography. In turn, she let Gould see the papers (and no one else has had access to these highly personal papers). Much of the history of Beebe and his professional and personal life has been lost, but Gould's book is an interesting read none the less.

By looking at the illustrators and visual media created during the Arcturus Expedition, we can see that during this period, the act of scientific exploration and discovery was not merely the act of finding, but of documenting; not only of describing but of preserving.

Thank you for your work. My father, Jay F.W. Pearson was on the expedition (I think he was 23 at the time--he was born 1901) and went on to help found the University of Miami in Coral Gables, Florida. He was the U of M's second president. It would be nice if your note "Jay F.W. Pierson- Assistant in Microplankton" could be corrected. Again, thanks.

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDelete