Okay, we're not actually that bad. Historians in general tend to be pretty quiet about making direct links and saying things like "nothing changes"- probably because we love the idea of subtle change. No situation is exactly the same, but I think we can learn something from examining history.

I've been thinking about this recently as I've read about the difficulties in establishing a major antarctic conservation zone. If you're unfamiliar with what has occurred, here it goes:

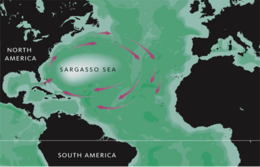

In July 2013, the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Living Marine Resources (CCALMR)- established in 1982 to safeguard Antarctic marine life- called a meeting between 24 nations and the European Union to try to designate one of the largest Marine Protected Areas (MPA) in the Antarctic Ocean. One area encompassing a portion of the Ross Sea, proposed by the United States and New Zealand, would cover 600,000 square miles; another in East Antarctica proposed by France, Australia, and the European Union would cover another 600,000. It would, if passed, have doubled the amount of MPAs in the world and been the largest protected ocean region in the world.

But it didn't pass.

There were some reservations before the meeting in July- America and New Zealand had already scaled back their proposal, which had originally included all of the Ross Sea. That area is especially important in these negotiations because it contains the fishing grounds for the Chilean Sea Bass (a very yummy, very non-sustainable ocean resource that can sell for upwards of 35$ a pound). As I've previously discussed on the blog, protecting marine fish stocks is very difficult because those suckers just swim everywhere and they don't really recognize man made borders. So, you can only protect those sea bass if they stick to the area you can get protected, and people who want to harvest these fish know it just as well as people who want to protect them.

And they aren't the only valuable resource in the Southern Ocean. Krill harvesting for animal feed and the Omega-3 fish oil dietary supplement market is on the rise. (I know all about this market as I'm a currently pregnant lady and those doctors push Omega-3 fish oils on you like, well, a pusher. Little did I know that those little pills could be filled with Southern Ocean krill!) With the warming oceans and the increase in krill fishing, scientists are in a race against time to establish baselines for a sustainable krill catch- first, they have to know a heck of a lot more about krill in general.

So when the meeting happened, things went south- and not in a good, let's-save-the-Southern-Ocean way. But in a Russia-and-the-Ukraine-are-questioning-the-legality-of-MPAs-to-try-to-block this-measure- kind of way. It's pretty clear that the CCAMLR has the legal standing, if they can get an accord, to establish MPAs. So why would Russia and the Ukraine try to block the MPAs? The larger issues for Russia were the size of the proposed area and the fact that a ban on fishing and harvesting within that region would be indefinite. And a big thing, they suggested their wasn't enough scientific evidence to make all of these waters protected indefinitely. We don't know much about baselines when it comes to these organisms, and a lot of what we know is rough data and guess work. One of the reasons that protection would be a good idea is that it would actually allow researchers the chance to study the area intensively without worrying about harvesting. Who is to say what over harvesting krill and sea bass looks like? Right now the data is rough at best and that could change if scientists get down there and find that stocks of krill are fine. But if they find that, it doesn't mean you can go harvest because now it is an MPA- I think you can see that this would be a problem- if there is a way to harvest krill sustainably in this area but we only discover that after we've blocked the region from fishing, we've cut off a huge supply of food from a lot of people. (also, there might be oil under the Southern Sea and we wouldn't want to leave that alone now would we) So. No. Go.

America and New Zealand have revised their proposal for a meeting next month in Hobart, Australia. The new proposal will start at 40% the second proposed size of the original, which was already smaller than the United States initially wanted (the entire Ross Sea) and this concession has angered many conservationists. But, we'll have to see what happens.

So, what about this situation reminds me of the past?

The situation in the Southern Sea reminds me a bit of another marine area with highly valued resources contested in the late 19th and early 20th century: The Pribilof Seal Islands in Alaska.

The United States purchased the Seal Islands from Russia in 1867, and by 1868 enterprising Americans (like their Russian counterparts before them) rushed to the islands to take advantage of a valuable resource that was considerably easier to mine than gold: the northern fur seal.

I think we're pretty familiar with what happens when people find a resource and harvest it unchecked: the fur seal almost went extinct twice. The incursion of Japanese, Russian, and English independent sealers nearly caused an outbreak of war over the territory. In other words, things got pretty hairy up north; but instead of allowing extinction, the concerned governments decided to try to scientifically figure out a baseline population that would make it possible to sustain a seal herd and allow a robust sealing season.

The United States Fish Commission set up a seal commission to investigate how many seals still lived in the herd, their breeding cycles and behaviors, statistics and birth records for each year, and any other data that might help figure out what a normal and sustainable herd of these animals might entail. Of course, they started gathering this data at an all time low of the population, so a lot of information gathered was historical in nature. Charles Townsend, then an investigator for the Bureau, was in charge of gathering as much historical data as possible about the fur seal herd, and he was incredibly interested in solving the mystery of how many fur seals had existed on the islands before they were decimated by humans.

He turned to some amazing sources of information. Townsend asked diplomats in Russia, Japan, Canada, and England to gain access to as many sealing vessel logbooks as they could and send him the numbers of seals taken for each season. This wasn't easy work for the diplomats and there were major gaps in the records, especially because there were so many independent sealing vessels that had made clandestine runs into the seal islands.

But some information trickled in, including data from England for the years 1894 and 1895.

.JPG) |

| Wildlife Conservation Society Archives Charles Townsend Files |

Townsend and the Commission wanted more accurate data about breeding habits and sex ratios and the impact of taking male versus female seals on the herd, but this data was somewhat difficult to come by. A request for a count of fur skins by sex was met with consternation: how does one tell the sex of a fur seal after death? Townsend claimed it was rather easy to tell the difference (nipples!) and sent along a particularly helpful circular outlining where one might look to find the answer, but in the end the data was still patchy.

.JPG) |

| Wildlife Conservation Society Archives Charles Townsend Files |

Many aspects of the seal herd and its behaviors remained contested. One particularly interesting question involved accidental infanticide. Some scientists claimed that it was important to thin the herd of seals, because if the population became too large, females were known to accidentally roll over onto their cubs and smother them to death (a fear I seriously am having). Eye witness accounts claimed they had seen accidental deaths occur in highly populated areas, and this suggested to some in the Commission that it would be healthiest to maintain a smaller number of seals in a given area to allow all individuals a chance at growing to adulthood. But other scientists claimed that these eye witness accounts were unreliable and that, if such deaths occurred, they were uncommon and a negligible loss compared to the losses suffered from over harvesting.

Fur sealing was a big industry, and the fight over the right to harvest seals was a huge international issue. The Pribilof Islands were not the only fur seal rookeries in the world, Russia, Japan, and Canada all had locations where seals were present and they looked into their rookeries during the same period- I have not been in those archives but I hope someone will write a book someday on the seal convention of 1911 because they would definitely have a reader here!

The Pribilof Commission started gathering data and working on American harvesting issues as early as 1898, but an international Convention was not signed between Russia, the United Kingdom, Japan, and the United States until 1911. That convention basically banned pelagic sealing and made it illegal for ports to take in illegally caught seal skins for processing (seal skin processing was just as big a business as the sealing itself). Each government agreed to patrol their own herds and waters for poachers and to cooperate internationally to prevent pelagic sealing. It's an involved convention and if you feel like reading it, go here. It's clearly written and very interesting.

You might still be wondering though, what does this have to do with current issues in Antarctic waters?

I think one of my concerns is that, in an effort to build MPAs, conservationists might be demonizing the industries that have grown up around the "blue economy". Is it wrong that certain companies want to harvest krill in the Southern Ocean- not necessarily. There is nothing inherently wrong about finding a natural resource and utilizing it. Of course, we would hope with the proper data and international agreements that people would follow the rules and only harvest in a sustainable way- but the very act of wanting to harvest does not make you a demon. Yes, Russia is a pain in the butt, but they aren't the only country that wants to harvest krill, and I'm sure they aren't the only country that is interested in oil under the Ross Sea. They are just a country that isn't afraid to say it- and that might be a good thing in the long run.

A lesson we might learn from the Pribilof Commission and the eventual Convention is a lesson in time and the scientific process. Understanding the ocean, its inhabitants, its resources, and how we can sustain harvesting without harming will take more time, and scientific effort, than merely setting up zones where no one can harvest. Focus should be on international data collecting and sharing in these areas, and long term scientific studies that can give us more information about the ecosystem and organisms involved. If we rely on scientific data to make claims about sustainability, it is important that we admit when more data is needed. And that takes so much time.

Yes, this is a dangerous statement. Global warming and new fishing technologies and methods mean that time is definitely not on our side. The ability to decimate an ecosystem is enhanced by a shifting climate and the ability to take larger and larger catches through updated tools- but there has to be something scientists can do to gather international data that would serve everyone's interest.

What does not help is setting up a dichotomy between industrial/commercial fishing interests and the scientific and environmental communities. The oceans have long been a valuable resource for humans of all nations- Americans overfish their own waters and have failed time and again to set sustainable baselines for catches- because industry and culture have trumped scientific data. We should recognize in Russia's concerns what we can see in ourselves- not pretend we are perfect scientific stewards of the sea.

The science of the sea is intimately entwined with feeding people on land and to pretend otherwise is to set up a harmful dichotomy that disallows conversation. Both Russia and the US (and all 24 countries and the EU gathered at these meetings) want one thing in the end- to not die on a wasted planet full of nothing but boiling oceans and toxic air. Work your way up from there and they'd like to figure out how to feed the world, by land or ocean, without turning those resources into boiling and toxic places. As we saw with the Pribilof Seals, once the US shut down the islands to outside sealers, these sealers got very good as sitting outside the protected zone and picking off seals in deeper international waters. This bears a striking resemblance to the ability to catch krill and sea bass outside the Ross Sea. If we concentrate too heavily on preserving area, instead of sustainable catches based on data that each nation will want to enforce, are we really doing anything that will help sustain these organisms- or are we just shutting down future conversations about actually protecting these resources?

International cooperation is the key to saving the Antarctic Conservation areas, not condemnation.

.JPG)